Four years between albums is a lengthy wait for a rock band. What took so long for Danger Days to see the light of day?

I think the Black Parade tour went a little longer than it should have by about six months. We were beat, so we took a break for about a year, and started writing again February 2009. We had talked a lot about what the sound was going to be like, and in a way we created the sound of the record before we’d even picked up our instruments.

We were looking to do a more stripped-down version of the band—we had done that cover of [Bob Dylan’s] “Desolation Row” for the Watchmen soundtrack, and that was a much rawer sound than you’re used to hearing from My Chem. It was a response to the epic-ness of The Black Parade. The touring cycle was so hard for us physically and mentally, we saw that record and that sound as the enemy.

When we got close to the end of mixing, we realized we didn’t have a full album. So we got together with [producer] Rob Cavallo to record one or two more songs at the start of 2010, and when we recorded the song “Na Na Na,” it really opened things up for us. A lot of the flashes of creativity that you hear on Black Parade weren’t evident on [the discarded material.] We wrote a few more, and after about four songs we realized we were knee-deep in a new record, and that was Danger Days.

Commercially, The Black Parade was a massive success for My Chemical Romance, but in recent interviews, you guys talk about it as if you regret the whole thing ever happened. How did a platinum-selling album evolve into “the enemy?”

It’s a record I feel really proud of, and I don’t like to talk shit on it at all. I think the regrets come from the amount of touring we did and how we set up that record, taking on the persona of this imaginary band, The Black Parade. That persona was very antagonistic, [both] to the audience and to the press. It was a negative vibe, and that was the state of mind we lived in for two years. If anything, that’s where the regret comes from.

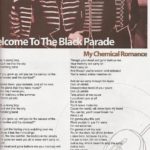

At its core, The Black Parade was an album about dying. How much of the negativity can be attributed to the subject matter?

You always have to listen to an album front to back to really get a sense of it, because the second half is where the ‘deep cuts’ are. With any record, most people only listen to the first four or five tracks. That’s true for a lot reviewers and listeners. Their idea of your music is [based on] the first four of five tracks and how you look in the videos. While The Black Parade dealt with death and [dark] subject matter, at the end of the record is the song “Famous Last Words,” which to me is the light at the end of the tunnel. The song’s message is very celebratory: “Get out and live your life.” The record plays out the way it does because it’s a journey. And not a lot of people want to take that roller-coaster ride, they only have 15 minutes to spend on a record.

Were you shocked with reaction of the British music press to The Black Parade?

We were paying a lot of attention to the press—it’s really hard not to. And they skewed very negative. We were being labeled as some kind of death cult. It was [being said] we were leading some sort of suicide revolution. And all this bullshit really weighed on us. It took its toll on the band. They didn’t get it. A lot of them deal in tabloid-ism and sensationalism. Papers like The Daily Mail, they’re not listening to the record, they’re going online and reading what other people are saying, and then it’s filtered down until they come up with their story.

We toured throughout Australia and Mexico, and we felt like we had targets on us. We were always going out there to prove something. That was the energy surrounding the touring of that record. We regret that all that stuff happened. There’s no regret about the music.